Part 3-Types Of Opal

TYPES oF OPAL

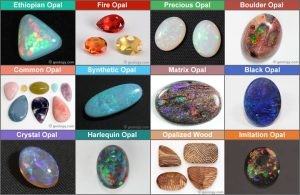

It is important to know the different types of opal in order to determine the value, quality and price. There are three distinct types of opal we will learn about: natural opals, composite or enhanced opals, and synthetic or man-made opals.

NATURAL OPALS

The four natural types of opal found are Black Opal, Boulder Opal, Crystal Opal and White Opal.

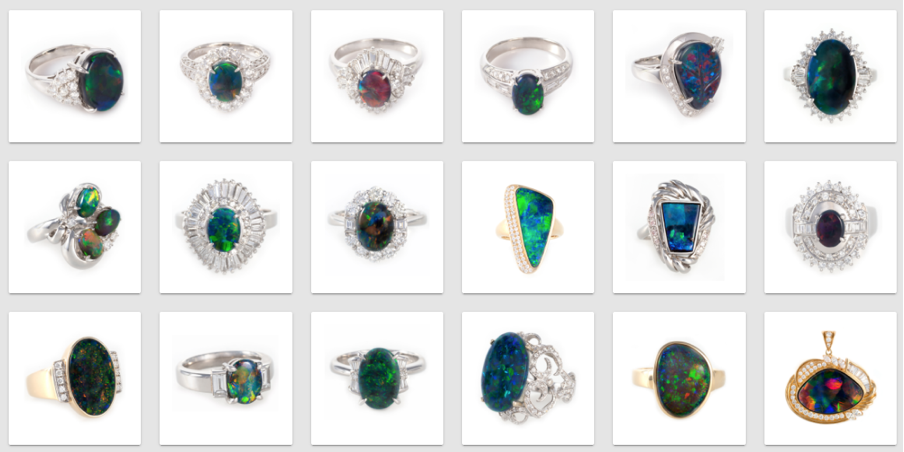

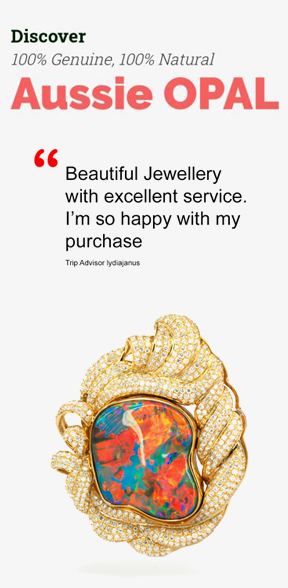

Black Opal

The queen of gems, black opal is the most popular, widely known opal coming from the town famous for its rich, rare and highly valuable opals, Lightning Ridge.

The opal forms in Iron Oxide called “potch” which can be black or grey. The potch is a non-precious form of opal exhibiting no play of colour. This is where the name Black opal comes from but an opal such as this with no colour is worth very little. The rarest black opals are known and loved for their vibrant colours often with all the colours of the rainbow and the colour is generally found as a colour bar (or bars) of various colours.

Black opal and boulder opal are the rarest of all opals found, amounting to only 10% of all opal mined. When black and boulder opal are cut the yield is only 5% which means a loss factor of 95%. In comparison to white opal which has a 50% loss factor you can see how this adds to the value of black opal.

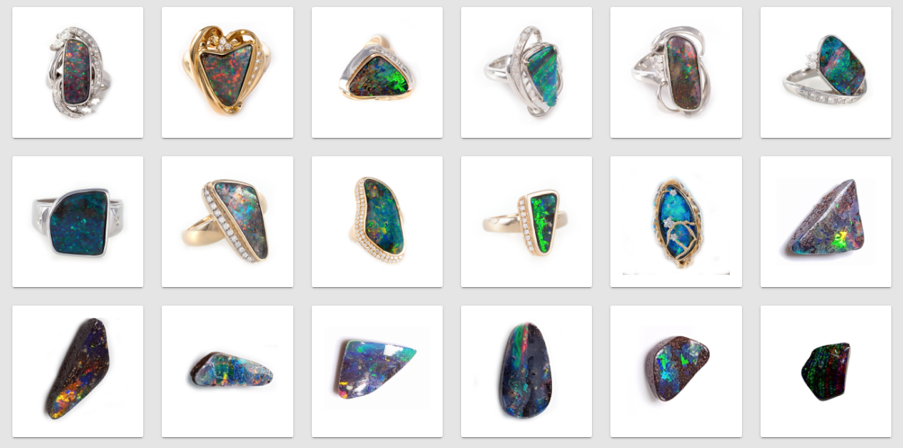

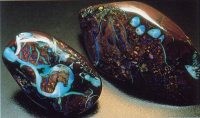

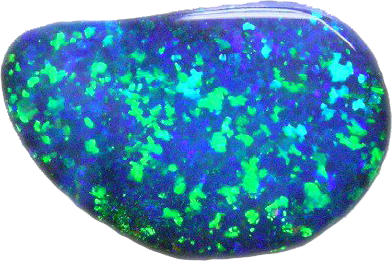

Boulder Opal

Found only in Queensland, Boulder opal (along with black opal) is enjoyed around the world as the rarest and most valuable of all opal. It forms in the cracks and crevices of the ironstone country of southwest Queensland.

The opal first flowed through the cracks of the boulders in liquid form thousands of years ago. With the passing of centuries the liquid material formed into solid opal with opal cutters now cutting these pieces into magnificent gems with the natural rock left on the back. Due to the dark backing provided by the ironstone, boulder opals generally have a dark body tone which leads to a vibrancy of colour similar to that found in black opals. Boulder opal generally is left in its individual shape and size it is found in, in comparison to the normal round and oval opals to highlight their individual beauty and to avoid unnecessary colour wastage.

With all opal mines slowly running out, Boulder Opal is the only opal that has been estimated to run out within the next 5 to 10 years. The reasons for this are because of native land titles in the Queensland Area and the increased damages being caused to the environment in order to mine Boulder Opal. It is estimated that for every 50 tonnes of dirt removed when mining boulder opal only one carat of fine Boulder opal can be found. Because of environmental concerns the government now requires the miners to rehabilitate the area which is proving to be a very expensive process. However, it’s not all bad news because these things together with limited supply of boulder opal are actually increasing the value by 25% every year for at least 10 years in a row. Needless to say, Boulder opal makes a sound long term investment.

Matrix Opal

Like boulder opal, matrix opal contains precious opal combined with its host rock. In matrix opal, however, the precious opal fills holes or pores between the host rock’s grains, creating a more even play-of-color throughout the stone instead of in distinct sections.

Matrix opal comes from Mexico, Honduras, and Australia. In Australia, Andamooka matrix opal is porous, so it’s easily (and often) chemically treated to improve its color. Honduras produces primarily matrix opal and their opaque variety typically has a dark host rock speckled with vibrant opal.

Matrix Opal: The specimen on the left is a cabochon cut from matrix opal mined at Andamooka, Australia. The specimen on the right is a bead cut from matrix opal mined in Honduras.

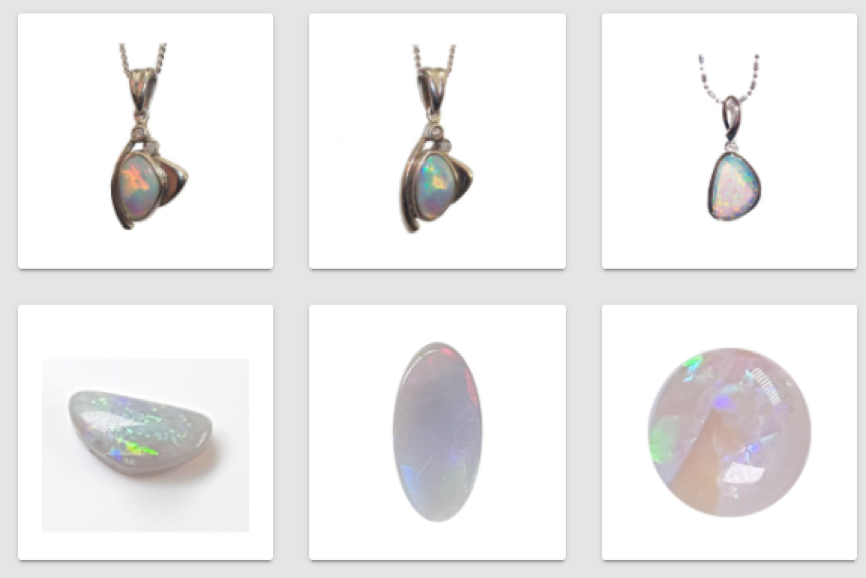

Crystal Opal

Crystal Opal, also known as Light opal, is the only opal formed from pure hydrated silica which means it is transparent.

Crystal opal is quite common, representing approximately 30% of opals mined and is found in Coober Pedy in South Australia. The translucence of a crystal opal often gives it a greater clarity and vibrancy of colour than opaque. Pale coloured crystal opals (white crystal opals) are generally more valuable than opaque white opals, and black crystal opals can often have more beautiful colour than opaque black opals.

Crystal opals are generally cut in a standard oval shape if possible, however if the nature of the stone dictates, sometimes a ‘freeform’ or teardrop shape is cut in order to maximise the size and carat weight of the stone. Crystal opals are also cut with a high cabochon if possible as this enhances the appearance of the colour. When cutting light opal we yield 50% which means we only have a 50% loss factor due to rock waste.

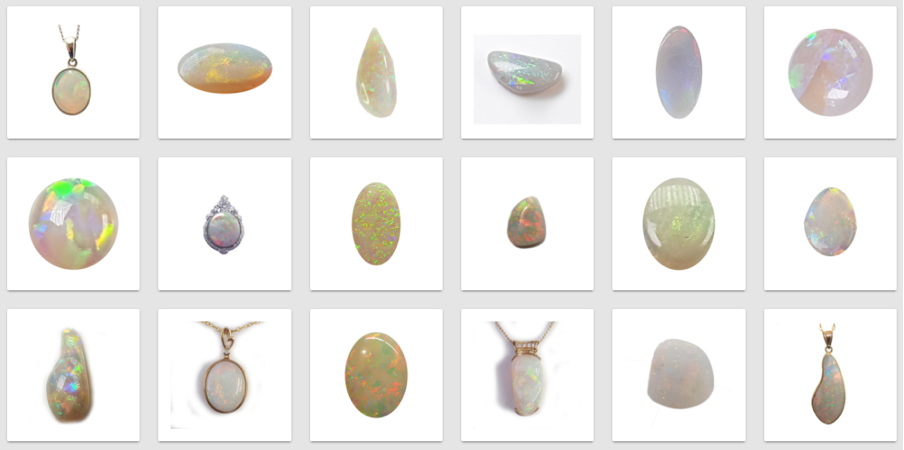

White Opal

The most common form of opal is Coober Pedy’s White Opal.

Representing approximately 60% of all opal mined, white opal is exported and recognized all over the world.

White opal contains Magnesium Oxide which is what gives the opal its white base. Because of their pale body tone, white opals generally have less vibrant colour than boulder opals and black opals. They do not have the advantage of having a dark or black background which enhances the stone and makes the opal colour stand out.

When a white opal is partially translucent, it enhances the clarity and vibrancy of the colour, and thus the value of the stone. Therefore a white opal which has some of the properties of a crystal opal will often have a higher value.

The home to the light opals, Coober Pedy was discovered in 1915. It is an isolated and rugged location with freezing nights, days where the temperature rarely drops below 40 degrees Celsius with bush flies by the million. Because it is too hot for life to exist comfortably on its surface, many homes have been built underground. Virtual palaces, a church and even a hotel have been built underground where the living temperature stays at a cool 20-24 degrees Celsius. A miner gouging out an underground dwelling can often find the exercise self-funding when he hits an opal seam. Today the opal fields in Coober Pedy are approximately 45 kilometers.

TYPES OF NATURAL OPAL

Natural opal is opal which has not been treated or enhanced in any way other than by cutting and polishing. There are three types of natural opal, with varieties described by the two characteristics of body tone and transparency.

COMPOSITE OR ENHANCED OPALS

Doublets

A great way to start enjoying opal at a fraction of the cost of a solid opal is to go for a composite or enhanced opal such as the doublet or triplet opal. A doublet opal, as the name suggests, consists of two layers. The first layer is a thin slice of natural crystal opal and the second layer can either be potch or ironstone – the natural backings that black and boulder opals originally form in. The crystal opal is stuck together with black cement and attached to the potch or ironstone in effect enhancing the colours and patterns of the crystal opal.

Doublets can usually be identified by looking at the side of the opal – if the layers are adhered together you will notice that the line where the coloured opal and the black backing meet is perfectly straight. This is necessary for the two layers to be adhered together. If a doublet is set into jewellery with the sides covered, it is extremely difficult, even for an expert, to tell whether it is a doublet or a solid opal. Since the top of the stone consists of pure opal, it therefore appears exactly like a black opal, and doublets thus have a much more natural appearance than triplets.

The two pictures shown here are of the same stone. The picture on the left shows the face-up appearance of the stone. The picture on the right is a side view. This stone is an opal doublet that was assembled from a thin layer of precious opal glued to a backing of host rock. In the side view you can clearly see the “glue line” between the two materials. If this stone was mounted in a setting with a cup bezel, it might be impossible to tell if it was a solid opal or a doublet.

Triplets

A triplet opal consists of three layers. It is in fact a doublet with a crystal quartz cap which adds the third layer and becomes known as a triplet. The crystal quartz cap sits on top of the thinly sliced crystal opal. It acts as a lens that magnifies and enhances the patterns and colours of the crystal opal.

Because triplet opals have a clear non-opal capping on top, it is easy for an experienced person to identify a triplet immediately by the appearance of the triplet opal. Triplets usually have a ‘glassy’ appearance and the light reflects differently from the top of the opal. You can look at the side of the stone to identify a straight line where all the layers meet, and also look at the back of the opal.

Triplets are generally the less expensive option out of the two because there is less weight of opal, however, of all the forms that opal is available, triplet opals, because of the higher refractive index of the quartz crystal cap and the magnifier effect of its domed shape – opal triplets show the most ‘bling’.

The two stones pictured are opal triplets produced by sandwiching a thin layer of precious opal between a backing of black obsidian and a cover made of clear synthetic spinel. The clear top acts like a magnifying lens and enhances the appearance of the thin precious layer. The black obsidian back provides a contrasting background that makes the play-of-color in the precious layer more obvious. If you look very closely at the inverted stone, you will see a tiny line of color that is the edge of a thin slice of precious opal.

TREATED OPALS

With the demand for vibrant gemstone growing almost daily, vendors must find new ways to push lower-quality stones into the upper echelon of the market; this has led to the rise in ‘gemstone treatments’. These are procedures that, as the name might suggest, are meant to enhance a gemstone’s appearance or stability. Although treated opals can look quite beautiful, ethical problems arise when a seller does not disclose the treatments used on their gemstone.

There are many different reasons why an opal would be ‘treated’. In recent years, various Queensland boulder opal specimens have been treated by the deposition of a layer of Aluminium oxide (Al2O3). This is done specifically to overcome the inherent softness of the opal.

Some opals are heat treated. An opal’s colour will be brighter when the surface is sprayed with a liquid such as water. Wetting the surface of a rock will only change the colour for as long as it takes for the liquid to dry; a more permanent solution is for the opal to be treated using heat and oils. Another permanent solution is to soak and simmer the stone in a sugar water solution for several hours, so that the acid in the liquid solution can carbonise, but this is usually only done to opal that as formed in sandstone, as the background colour of sandstone is quite light meaning the opals colour does not appear as vibrant. The end result of this procedure is that the colours of the opal will be much more vibrant, giving the appearance of a black opal.

The action of treating an opal is not inherently bad, it is only when these opals are then marketed as otherwise, and people are deceived, that this becomes a problem.

Sugar and acid treatment is one of the most commonly used methods to enhance opal. In the trade, this treatment is usually applied to matrix opal from Andamooka, Australia, a particularly porous material. The finished product is often referred to as “Andamooka matrix opal” or “Andamooka rainbow matrix opal” by the trade. This treatment was presented as a hot sugar bath followed by a hot acid bath. The chemical reaction between sugar and acid then deposits carbon to the porous structure of the opal as black dots. The treatment darkens the background color of the opal and therefore makes the play-of-color stand out more. After the final cooling, the materials were polished to finished products or retreated if necessary, revealing a dramatic change from start to finish (see photo).

Dyed Hydrophane Opal

Hydrophane opals, commonly found in Ethiopia, readily absorb liquids through their permeable matrix, making them easy to treat with dyes. These dyed opals can exhibit striking hues when strong, vibrant colorants are used. Even individuals familiar with opal can often recognize these unmistakably bold colors on sight. However, subtle enhancements to an opal’s natural color may go unnoticed without closer inspection.

Careful microscopic examination is one way to identify dyed opal, especially when the color is concentrated near the surface or along fractures. In some cases, gemologists or large jewelry retailers request samples of the uncut rough from their suppliers. By comparing the rough with the finished stones, they can detect discrepancies in color that might indicate dye treatment.

For collectors and enthusiasts who specifically want natural opal, testing for dye is vital. Even slight enhancements can affect a stone’s authenticity, quality, and long-term value. Conversely, when disclosed, dyed opal can still be appreciated for its unique colors, provided the buyer understands and accepts the nature of the treatment.

Although dyeing can produce an initially attractive appearance, the results are not permanent. Exposing dyed opal to strong daylight and general wear often causes the color to fade or become patchy within a few months. Prolonged exposure to water and certain chemicals can also accelerate the fading process, as the color agents gradually leach out. If you own or plan to purchase dyed opal, keep in mind that proper care — such as protecting the stone from harsh environments — can help preserve its appearance, even if only for a limited time.

Dyed Hydrophane Opal Testing

From 2015 to 2017, a jewelry designer reportedly purchased over 500 carats of vivid pink and blue opals from a dealer she met at a small regional gem show in California. The dealer did not disclose that the material was dyed and claimed that these intense colors were from a new opal discovery in Mexico. This kind of misrepresentation could damage consumer confidence in all opals.

In July 2017, author EB received the two opals in figure 1 for examination. After determining that they were likely color treated, he sent both samples to GIA’s Carlsbad lab for further testing. With permission from the owner, each opal was cut in half to obtain a control sample and a test sample. The test samples (one blue and one pink) were soaked in acetone and 3% hydrogen peroxide solutions to determine if their colors were stable. Their color saturation was significantly reduced, with the blue half turning white and the saturated pink half becoming very light pink (figure 2). It is possible that more time in the solution would have further reduced the pink color. These two opals were carefully examined and were consistent with hydrophane opal from Ethiopia that had been dyed.

Note that even though the samples lost their color, the dye molecules were not removed. But the hydrogen peroxide had oxidatively decomposed the dye into different molecules that did not absorb visible light and therefore could no longer impart color on the opals.

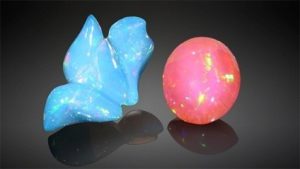

Figure 1: These two opals (21.75 and 15.12 ct) were represented as natural-color blue and pink opal from Mexico. Photo by Robison McMurtry.

Figure 2: The blue and pink opals were confirmed to be dyed hydrophane opal, likely from Ethiopia. Half of each stone has been bleached using 3% hydrogen peroxide solution. Photo by Robison McMurtry.

Click here to read about a Large Oolitic Opal Block – A relatively new kind of black opal that appears to be treated but is NOT!

SYNTHETIC OR MAN-MADE OPALS

Synthetic Opal

“Synthetic opal”, “lab-created opal”, “lab-grown opal”, and “man-made opal” are some of the names used for opal which has been made by humans. This type of gemstone is created in controlled laboratory conditions. They have the same chemical composition, physical properties and appearance of natural opal. These man-made opals can have spectacular play-of-color and beauty that rivals some of the best natural opals, and they usually sell for a much lower price.

The laboratory opal producing process was first invented by Pierre Gilson, Sr. of France in 1974. This process produces a kaleidoscope of colours from the rare and precious black opal to crystal and white opal. The Gilson formula is considered the truest gemological process in the world today, considered by many gemologists to be the world’s finest laboratory grown opal. The process takes from 14 to 18 months, and the colours are natural with no treatment or enhancements.

Monarch Opal

This new man made synthetic opal is popular in low end silver settings as the designs and patterns look amazing with veined potch lines. Many online sites and retailers sell it as Monarch Opal and do not inform buyers if it is man made, synthetic or natural. When buyers ask about this opal in a setting they are told it is simply Monarch Opal. It has also been given the names of Galaxy Opal, Monet Opal and Exodus Opal.

To be accurate, this Opal is actually called Sterling Opal. The names above such as Monarch Opal are trade names given to the different varieties of Opal that they can create.

Imitation Opal

“Imitation opals” are natural or man-made materials that have an appearance that is similar to natural opal. Man-made imitation opals are usually made of glass, resin or plastic. They are not natural opals and must be sold with a disclosure that clearly communicates to the buyer that the item is an “imitation opal” or an “opal-like product” or an “opal imitation”. Imitation opals are used as a low-cost substitute for natural opals. They can be as beautiful as natural opals and can sometimes fool an experienced gemologist if they are well made.

Imitation opals have been made since the 1960s. They are becoming more common in the gem and jewelry market, and their appearance is becoming harder to distinguish from natural opal. Many people enjoy their appearance and appreciate their lower cost. They sometimes are sold under trade names that include “Opalite” or “Opal Essence” or “Aurora Opals”. Imitation opals are beautiful and legitimate products if they are sold with clear disclosure.

Synthetic Opal Color Samples: A sample card displaying a collection of synthetic opal cabochons of various colors. This collection clearly illustrates the abilities of a synthetic opal manufacturer.

PRECIOUS OPAL

“Precious opal” flashes iridescent colors when it is viewed from different angles, when the stone is moved, or when the light source is moved. This phenomenon is known as a “play-of-color.” Precious opal can flash a number of colors such as bright yellow, orange, green, blue, red or purple. Play-of-color is what makes opal a popular gem. The desirability of precious opal is based upon color intensity, diversity, uniformity, pattern and ability to be seen from any angle.

Precious opal is very rare and found in a limited number of locations worldwide. Most precious opal to date has been mined in Australia. Ethiopia and Mexico are secondary sources of precious opal. Precious opal is also mined in Brazil, the United States, Canada, Honduras, Indonesia, Zambia, Guatemala, Poland, Peru, and New Zealand.

Harlequin Opal

“Harlequin opal” is a name given to an opal that displays patches of color in the shape of rectangles or diamonds.

The “Harlequin” color pattern is normally exhibited in two dimensions on the face of the stone. However, less often the color patches can be seen within a transparent stone – in a three-dimensional display. This is what you will see in the stone in the accompanying image.

Pinfire Opal (aka Pinpoint Opal)

“Pinfire opal” is a name used for opal that has pinpoints of color throughout the stone. The opal on the left is a pinfire opal cut from material mined at Coober Pedy, Australia. The stone on the right is a pinfire opal from the Constellation Mine in Spencer, Idaho. It is 6 millimeters by 4 millimeters in size.

COMMON OPAL

“Common opal” does not exhibit “play-of-color.” It is given the name “common” because it is found in many locations throughout the world. Most specimens of common opal are also “common” in appearance and do not attract any commercial attention.

However, some specimens of common opal are attractive and colorful. They can be cut into gemstones of beauty that accept a high polish. They can be attractive and desirable – but they simply lack a play-of-color that would earn them the name “precious.” Common opal is frequently cut as a gemstone and can command reasonable prices.

Pink Opal

Pink opal is a common opal in pale to bubblegum pink, though other colors like white, yellow, peach, lavender, and black may appear as well. This opal type commonly has inclusions that create dark streaking or color zones.

Pink opals come from Australia, Mexico, and the USA, but Peru is the most prolific source. Peruvian pink opals have a milky tone and vivid, uniform color, particularly “pink Andean opal.”

Western Australia’s pink opals are actually opalized radiolarite and often heavily included (meaning they have trace quantities of other minerals or debris), creating white, brown, or black patterns.

Morado Opal

Morado opal, also called “purple opal” or “Opal Royale,” is a purple common opal variety native to Mexico. The colors range from lavender to violet, and are typically milky and opaque in tone. Purple hues also appear in Tiffany opal, an opal fluorite conglomerate from Utah, USA, colored purple by fluorine gasses.

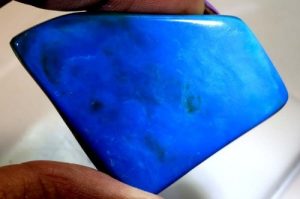

Blue Opal

Blue opals can be common or precious, ranging from deep teal to pale sky-blue. Peru is largely tied to this variety, and “blue opal” often refers to Peruvian common blue opal. Peru also produces precious blue opal, and some stones have play-of-color in small zones.

Brazil joins Peru in producing a rare blue-green opal called Paraiba opal. Other blue opal mines are in Slovakia, Indonesia, and the USA, including Oregon’s pastel blue Owyhee opals.

Dendritic Opal

Also called “moss opal,” dendritic opal is a white or yellow-brown type of common opal characterized by green or brown moss-like (dendritic) inclusions. These inclusions, often manganese or iron, form unique patterns, including those reminiscent of a forest landscape seen in “landscape opals.”

Dendritic opals can be nearly 30 percent water, which classifies them as “soft gems.” Most of these opals come from Australia, Mexico, or the USA, but you can also find them throughout Central America, Asia, and Russia.

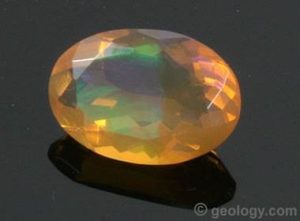

FIRE OPAL

“Fire Opal” is a term used for colorful, transparent to translucent opal that has a bright fire-like background color of yellow, orange or red. It may or may not exhibit “play-of-color.” The color of fire opal can be as vivid as seen in the three stones shown here.

Some people are confused when they hear the name “fire opal.” They immediately expect the “play-of-color” found in precious opal. The word “fire” is simply referring to the red, orange, or yellow background color.

Fire opal might exhibit play-of-color, but such a display is usually weak or absent. Fire opal is simply a specimen of opal with a wonderful fire-like background color. The color is what defines the stone.

Fire Opal

Do you love a fiery spectacle? You’ll find precisely that in fire opals. Fire opals come in red, orange, yellow, and brown body colors and can be either common or precious. Originating in Mexico, these stones are often called Mexican fire opals, though they also come from Australia and Ethiopia.

Fire opals differ from most opals in being translucent to transparent (not opaque) and forming inside volcanoes. Most Mexican fire opals are common opals, but Ethiopia produces precious fire opals with neon violet and green color flashes.

PRECIOUS FIRE OPAL

If you understand the difference between “precious opal” and “fire opal,” here is another variation. This opal from Ethiopia has an orange bodycolor, making it a “fire opal,” and it also contains an electric green to purple play-of-color, making it a “precious opal.” So, we might call this a “precious fire opal.” Much of the Ethiopian opal currently being produced has yellow, orange or reddish bodycolor, along with play-of-color, that allows it to be called “precious fire opal.”

OTHER TYPES OF OPAL

Opalized Wood

Opalized wood is a type of petrified wood that is composed of opal rather than chalcedony or another mineral material. It almost always consists of common opal, without play-of-color, but rare instances of petrified wood composed of precious opal are known. Petrified wood composed of opal is often thought to be composed of chalcedony because many people do not know that petrified wood can be opaline. These two types of silicified wood can be easily separated by testing their hardness, specific gravity, or refractive index.

Mookaite Opal

“Mookaite” is the trade name for an opaque gem material with spectacular color patterns that is mined in Western Australia. Gemological testing identifies most mookaite as a chalcedony. However, some mookaite has the refractive index and specific gravity of opal. The cabochon on the left has the familiar color pattern of mookaite. The cabochon on the right has the less-familiar brecciated appearance. Both can be properly called “common opal”.

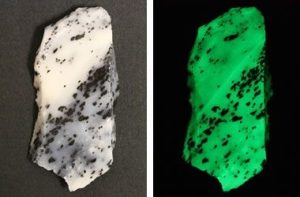

Fluorescent Opal

Most opal will glow or fluoresce weakly under an ultraviolet lamp. However, some specimens exhibit a spectacular fluorescence. This specimen of mossy common opal rough from Virgin Valley, Nevada fluoresces a brilliant green under UV light. The photo on the left was taken under normal light, and the photo on the right was taken under a short-wave ultraviolet lamp.

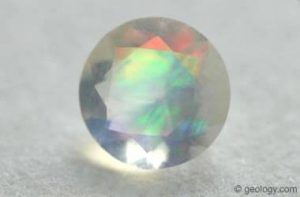

Contra-Luz Opal

Translated from Spanish as “against light”, “Contra-Luz” is a colorless and intriguing variety of opal that best displays play-of-color when the light source is behind the stone and the light travels through the stone and into the eye of the observer.

Because the contra-luz effect only occurs when light travels through the stone, a contra-luz opal must be transparent or semi-transparent.

Utilizing contra-luz opal in jewelry requires a setting that allows light to pass through the stone. An example would be a pair of earrings made using beads of highly transparent contra-luz opal that dangle below the ear lobes. Light passing through the beads will produce a display of color when the observer, the light source, and a bead are in alignment.

Opalite

The name “opalite” has been used in two ways. Its original use was for common opal without play-of-color. That definition of opalite has been published in geology and gemology glossaries for decades. In the 1980s, the name “opalite” started to be used as a marketing term for a plastic imitation opal with true play-of-color. That use has since spread to a variety of plastic and glass materials that look like opal or have an opalescent appearance.

OPAL NAMES BY LOCATION

Andamooka Opal

Andamooka is one of the early mining districts of South Australia. Commercial production began there in the 1920s. The area is famous for its matrix opal – with the play of color distributed through a matrix of limestone, sandstone or quartzite. The stone in the photo is a cabochon cut from Andamooka matrix and weighs about 30 carats.

Ethiopian Opal

Gem-quality opal from Ethiopia began entering the market in significant amounts starting in 1994. Since then, additional opal deposits have been discovered that might be large enough in size to take significant market share away from Australia, which has supplied nearly 100% of the opal market for over 100 years. Precious opal, fire opal, and very attractive common opal are all being produced in Ethiopia. They are becoming more abundant in the gem and jewelry market and more popular with consumers.

Louisiana Opal

“Louisiana opal” is a quartzite cemented with precious opal that has been mined in Vernon Parish, Louisiana. On close examination you can clearly see quartz grains with the spaces between them filled with a matrix of clear cement that produces a play-of-color in incident light. It is a stable material that can be cut into cabochons, spheres and other objects. Some of the material is brown like the 20mm x 20mm cabochon pictured, but it also occurs in a gray to black color that makes the play-of-color easier to see.

Peruvian Opal

Peru produces some of the world’s most beautiful opal. It is not play-of-color opal; instead, it is common opal of uncommon color. Opal mines in Peru yield common opal in pastel colors of blue, green, and pink. The accompanying photo shows strands of rondelle-shaped beads in all three colors. Play-of-color is not needed to have beauty in common opal. The beads in the photo are about seven millimeters in diameter. Peruvian opal is also used to make beautiful cabochons and tumbled stones.

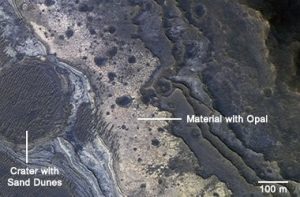

OPAL ON MARS?

In 2008, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter discovered a number of opal deposits on Mars. In this satellite image, the surface in the pinkish cream-colored area to the right of the impact crater is covered with hydrated silica rock debris that we would call “opal.” Mars researchers have also identified layers of opal exposed in the outcrops of crater walls. Since opal is a hydrated silicate its formation requires water. So, the discovery of opal on Mars is another evidence that water once existed on the planet.

REFERENCES

Geoscience News and Information. https://geology.com/gemstones/opal/

Australian Opal Centre. https://www.australianopalcentre.com/opal